The bond between a child and their primary caregiver is one of life’s most fundamental connections. This early relationship forms a blueprint for future emotional and social development. Psychologists call this blueprint an attachment style. A secure attachment provides a safe base for a child to explore the world. However, when this bond is inconsistent or stressful, it can lead to insecure attachment. Understanding its impact is crucial for supporting a child’s healthy development.

The Attachment Theory Workbook: Powerful Tools to Promote Understanding, Increase Stability, and Build Lasting Relationships (Attachment Theory in Practice) provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through attachment theory challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. The Attachment Theory Workbook: Powerful Tools to Promote…. How To Heal An Anxious Attachment Style: A Self Therapy Journal to Conquer Anxiety & Become Secure in Relationships provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through healing anxious challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. How To Heal An Anxious Attachment Style: A Self Therapy J…. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized Attachment Recovery Workbook: Apply Attachment Theory to Understand Your Behavior Patterns, Improve Emotional Regulation, and Build Secure & Healthy Relationships provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through avoidant disorganized challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized Attachment Recovery W…. Overcoming Insecure Attachment: 8 Proven Steps to Recognizing Anxious and Avoidant Attachment Styles and Building Healthier, Happier Relationships provides valuable support and resources for insecure to, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Overcoming Insecure Attachment: 8 Proven Steps to Recogni…. Disorganized Attachment: Move Beyond Your Fear of Abandonment, Intimacy, and Build a Secure Love Connection provides valuable support and resources for disorganized attachment, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Disorganized Attachment: Move Beyond Your Fear of Abandon…. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It …. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment styles, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It …. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. The Attachment Theory Journal: Prompts and Exercises to Promote Understanding, Increase Stability, and Build Relationships That Last (Attachment Theory in Practice) provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through attachment theory challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. The Attachment Theory Journal: Prompts and Exercises to P…. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications offers comprehensive information and strategies for navigating attachment theory, providing valuable insights and practical advice for your journey. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Ap…. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It ….

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Insecure attachment is not a sign of bad parenting. Instead, it reflects a pattern of interaction where a child does not feel consistently safe, seen, or soothed by their caregiver. Consequently, the child develops coping strategies to manage this relational stress. These strategies manifest as distinct attachment styles.

The Three Faces of Insecure Attachment

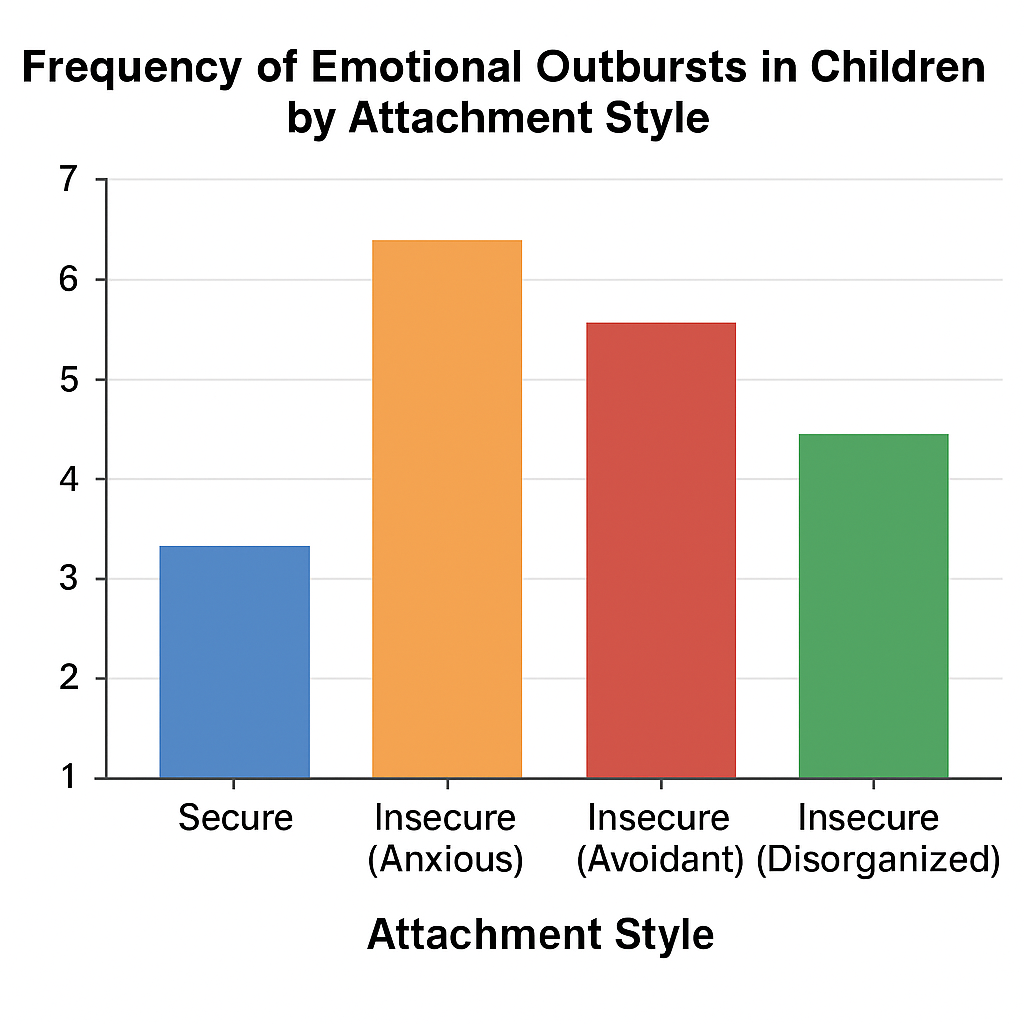

Experts generally categorize insecure attachment into three main types. Each type develops from a different pattern of caregiver-child interaction and results in unique behavioral patterns.

Anxious Attachment

When a child develops an anxious attachment style, their early experiences with caregivers are often characterized by a bewildering pattern of availability. Imagine a child navigating a world where the most important person in their life is a flickering light – sometimes bright and comforting, other times dim, absent, or even overwhelming.

This inconsistency stems from what’s known as inconsistent caregiving. It’s not necessarily a lack of love, but rather a fluctuation in how that love and support are expressed:

- Responsive and Nurturing Moments: At times, the caregiver might be perfectly attuned, offering warmth, prompt comfort, and engaging interaction. They might respond quickly to a cry, offer a reassuring hug, or join in play with enthusiasm.

- Unavailable or Intrusive Moments: At other times, the same caregiver might be physically or emotionally distant. This could manifest as:

- Emotional Unavailability: Distracted by their own stressors, phones, or other demands, leading them to be physically present but emotionally absent.

- Physical Absence: Frequent or unpredictable departures without clear explanations or reliable returns.

- Intrusiveness: Overwhelming the child with attention when it suits the parent, not necessarily when the child genuinely needs it, or taking over the child’s play in a controlling way.

This unpredictability creates a profound sense of unease. The child struggles to form a consistent mental model of their caregiver as a reliable source of comfort and security. They are left in a constant state of hypervigilance, perpetually scanning their environment for cues about whether their caregiver will be there for them this time. This uncertainty fuels deep-seated anxiety about their caregiver’s availability, leading to a profound lack of safety and trust in the relationship.

As a direct consequence of this emotional rollercoaster, children with an anxious attachment style often exhibit specific behaviors:

- Clinginess: They may become excessively reliant on physical proximity to their caregiver, afraid to explore independently or play alone. This isn’t just a preference; it’s a desperate attempt to control the caregiver’s presence and prevent perceived abandonment. Brief separations can trigger intense distress, and they might “shadow” their parent, always needing to be within sight or reach.

- Difficulty Soothing: Even when the caregiver is present and attempting to comfort them, these children can be challenging to calm. Their internal alarm system is so finely tuned and frequently triggered that it’s hard for them to de-escalate. The comfort might feel temporary or insufficient, as they’ve learned not to fully trust its lasting presence.

Crucially, these children learn a specific, albeit unconscious, strategy to ensure their needs are met: they must amplify their distress. A quiet whimper or a subtle request for attention often goes unnoticed in the inconsistent environment. Therefore, the child learns that to break through the caregiver’s potential unavailability, they need to escalate their emotional expression. This can manifest as:

- Intense crying that quickly turns into screaming

- Repeated, urgent calls for attention

- Dramatic physical displays like throwing themselves on the floor or hitting (not out of malice, but out of desperation for connection)

This learned behavior ultimately leads to heightened emotional reactions. The child lives in a state of emotional overdrive, struggling significantly with emotional regulation. They might experience:

- More frequent and intense tantrums or meltdowns

- Extreme swings between sadness, anger, and fear

- Difficulty calming down once upset

- Anxiety that manifests physically, such as stomach aches or sleep disturbances

Their emotional world becomes a constant battle, as they try to manage internal turmoil without a consistently reliable external source of co-regulation.

Avoidant Attachment

Here’s an elaboration on avoidant attachment in children:

The Roots of Avoidant Attachment: Distant Caregiving

Avoidant attachment patterns often emerge from a specific type of caregiving environment characterized by consistent unresponsiveness or outright rejection of a child’s natural bids for closeness and comfort. This isn’t about occasional lapses, but a pervasive dynamic where:

- Emotional Needs Are Minimized: A child’s cries, fears, or requests for a hug might be met with impatience, dismissal (“You’re fine, stop crying”), or even subtle annoyance.

- Physical Affection is Scarce or Conditional: Caregivers may be uncomfortable with physical closeness, offer it sparingly, or only when the child is “behaving” rather than when they are genuinely distressed.

- Premature Independence is Encouraged: Children might be pushed to be self-sufficient far too early, with messages like “big kids don’t need help” or “handle it yourself,” subtly shaming their dependency.

- Caregiver Discomfort with Emotions: The parent or primary caregiver might struggle with their own emotions, making them ill-equipped or unwilling to soothe a child’s strong feelings. They may become overwhelmed or withdraw when the child expresses sadness, anger, or fear.

In such scenarios, the child learns a harsh lesson: expressing vulnerability or seeking connection leads not to comfort, but to further distance, rejection, or even punishment.

The Child’s Survival Strategy: Suppressing Needs

When a child’s innate need for comfort and closeness is repeatedly unmet or rebuffed, they are forced to adapt. To maintain some form of proximity to their caregiver – essential for survival – they develop a powerful deactivation strategy. This means they learn to:

- Suppress Their Attachment System: They effectively “turn off” or dampen their natural biological drive to seek comfort and protection from caregivers when distressed. It’s a painful but logical adaptation: if seeking help makes things worse, stop seeking.

- Internalize Emotional Self-Reliance: The child comes to believe that their needs are a burden, that they are inherently “too much,” or that no one will reliably be there for them. They learn to rely solely on themselves for emotional regulation, even when they are too young to do so effectively.

Observable Behaviors: The “Independent” Facade

On the surface, children with an avoidant attachment style often appear remarkably self-sufficient and emotionally contained. Their behaviors might include:

- Extreme Independence: They may prefer to play alone, rarely bring their problems to adults, and seem unfazed by separation from caregivers, even in new or stressful environments.

- Emotional Flatness: When hurt or upset, they might not cry, or their distress may be very brief and quickly suppressed. They might quickly change the subject if emotions arise in conversation.

- Refusal of Comfort: If offered comfort after a fall or disappointment, they might push away the caregiver, turn their head, or insist they are “fine” even when clearly not.

- Focus on Tasks/Objects: In stressful situations, they may direct their attention to toys or activities rather than seeking interaction or reassurance from adults.

- Limited Emotional Expression: They may struggle to identify or articulate their own feelings, often appearing stoic or detached.

While these behaviors might seem admirable in a culture that often values independence, they are a defensive mechanism, not a sign of true emotional resilience.

Beyond the Surface: Hiding a Deep Need for Connection

The apparent self-reliance is a carefully constructed shield. Beneath this seemingly independent exterior lies a child who deeply craves connection but has learned that expressing this need is unsafe. They are not genuinely independent in an emotional sense; they are actively hiding their vulnerability to avoid the anticipated pain of rejection.

- Fear of Rejection: The underlying fear is that if they show their true needs, they will be met with discomfort, disapproval, or withdrawal from the very people they depend on.

- Internal Conflict: They live with an internal conflict between their biological drive for closeness and their learned expectation that closeness leads to pain. The brain, in its effort to protect the child, prioritizes avoiding pain.

The Profound Cost of Emotional Self-Containment

This emotional self-containment, while a brilliant survival strategy in a challenging environment, comes at a significant and lasting cost to the child’s development and well-being:

- Impaired Emotional Literacy: Children may struggle to recognize, understand, and express their own emotions, leading to emotional numbness or difficulty processing complex feelings.

- Difficulty with Intimacy: As they grow, forming deep, trusting, and intimate relationships can be challenging. They may fear vulnerability and struggle to let others get close, perpetuating a cycle of emotional distance.

- Increased Internal Stress: Suppressing natural attachment needs is physiologically taxing. It can lead to higher levels of stress hormones and internal tension, even if outwardly calm.

- Reliance on Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Without healthy ways to process emotions or seek support, older children and adults with avoidant attachment may turn to maladaptive coping strategies like overworking, substance use, or isolating themselves.

- Missed Opportunities for Co-Regulation: They miss out on the vital experience of having a caregiver help them soothe and regulate their emotions, a foundational skill for emotional resilience.

Ultimately, while the child’s strategy allows them to navigate an unresponsive environment, it leaves them feeling fundamentally alone, carrying the silent burden of unmet needs and a deeply ingrained distrust of emotional connection.

Disorganized Attachment

Understanding the Roots of Disorganized Attachment

Disorganized attachment emerges from a profound psychological paradox that creates lasting confusion in a child’s developing mind. Unlike other attachment styles that follow predictable patterns, this style develops when children experience their primary caregiver as both their protector and their threat.

Common Scenarios That Lead to Disorganized Attachment

Several situations can create the conditions for this attachment style to develop:

Caregiver Trauma and Mental Health Issues:

- Parents struggling with untreated PTSD may have sudden emotional outbursts or dissociative episodes

- Caregivers with severe depression might alternate between emotional unavailability and overwhelming neediness

- Substance abuse can create erratic, frightening behavior patterns that confuse children

Unresolved Grief and Loss:

- A parent mourning the death of another child may unconsciously see the living child as a reminder of their loss

- Caregivers who experienced childhood trauma themselves may be triggered by their own child’s needs

- Parents dealing with recent divorce, job loss, or other major life changes may become emotionally volatile

Domestic Violence and Abuse:

- Children witnessing violence between caregivers experience terror while simultaneously needing comfort

- Direct abuse creates the ultimate contradiction where the source of pain is also the expected source of healing

- Emotional abuse through threats, intimidation, or extreme unpredictability keeps children in constant fear

The Child’s Internal Conflict

The child experiencing disorganized attachment faces what researchers call “fright without solution.” Their biological programming tells them to:

- Seek proximity when distressed (natural attachment behavior)

- Flee or freeze when faced with danger (survival instinct)

- Look to their caregiver for safety and regulation

When the caregiver is simultaneously the source of both comfort and fear, these three drives create an impossible situation with no clear resolution.

Behavioral Manifestations in Daily Life

Children with disorganized attachment display a wide range of confusing behaviors that often puzzle parents, teachers, and even mental health professionals:

Approach-Avoidance Patterns:

- Running toward a parent after a nightmare, then suddenly stopping mid-stride and backing away

- Reaching out for a hug while simultaneously turning their face away

- Asking for help with homework but becoming aggressive when the parent approaches

Dissociative Responses:

- Staring blankly into space during stressful moments

- Appearing to “check out” mentally during family conflicts

- Showing no emotional response to situations that would typically upset children

Controlling Behaviors:

- Attempting to manage their caregiver’s emotions through excessive compliance

- Taking on a parental role, such as comforting the adult during their distress

- Becoming hypervigilant about the caregiver’s mood and adjusting their behavior accordingly

Physical Manifestations:

- Repetitive self-soothing behaviors like rocking, head-banging, or hair-pulling

- Freezing in place when the caregiver enters the room

- Collapsing or going limp when picked up, as if giving up on seeking comfort

The Long-term Impact on Development

Disorganized attachment doesn’t just affect the parent-child relationship—it creates ripple effects throughout the child’s development:

- Emotional regulation becomes extremely difficult as the child never learned to use their caregiver as a safe harbor for co-regulation

- Social relationships suffer because the child’s internal working model of relationships involves fear and unpredictability

- Self-concept develops around themes of being bad, dangerous, or unworthy of consistent love

- Academic performance may decline due to the mental energy spent on hypervigilance and emotional survival

Understanding these complex dynamics is the first step toward healing, as it helps both caregivers and children recognize that these behaviors are adaptive responses to impossible circumstances rather than character flaws or deliberate defiance.

The Developmental Impact of Insecure Bonds

An insecure attachment style is more than just a label. It profoundly affects how a child learns to navigate their inner world and their relationships with others. The coping strategies learned in infancy ripple outward, touching every aspect of development.

Challenges with Emotional Regulation

The profound influence of a child’s early attachment experiences on their emotional regulation cannot be overstated. It lays the groundwork for how they perceive, process, and respond to their inner world of feelings.

The Foundation of Secure Attachment: Learning Emotional Resilience

When a child forms a secure attachment, they internalize a powerful truth: their emotions, no matter how big or overwhelming they might feel, are temporary, manageable, and worthy of attention. This vital lesson isn’t taught through lectures but through consistent, responsive interactions with a primary caregiver.

- Co-Regulation in Action: A securely attached child learns that when they’re distressed (e.g., scared, frustrated, sad), a trusted adult will step in to help them navigate those feelings. This process, known as co-regulation, involves the caregiver:

- Acknowledging and Naming Feelings: “I see you’re really frustrated that your blocks fell down.”

- Providing Comfort and Soothing: Offering a hug, a gentle voice, or a calming presence.

- Helping Problem-Solve (if appropriate): “Let’s try building it this way together.”

- Modeling Calm: The adult’s calm demeanor helps the child’s nervous system settle.

- Building an Internal Toolkit: Through repeated experiences of co-regulation, children gradually develop their own internal capacity for self-regulation. They learn that emotional storms pass, and they can draw upon the comforting template of their caregiver’s responses to soothe themselves. This leads to:

- Emotional Literacy: The ability to identify and understand their own emotions.

- Adaptive Coping Strategies: Learning healthy ways to express and deal with difficult feelings.

- Resilience: The capacity to bounce back from emotional setbacks.

The Struggles of Insecure Attachments: When Emotional Tools Are Missing

Without the bedrock of secure attachment, children are left without these essential emotional tools. They often struggle to make sense of their internal experiences, leading to significant distress and maladaptive coping mechanisms.

**Anxious Attachment: Amplified Distress for Connection**

Children with an anxious attachment often live with an underlying fear of abandonment or rejection. Their emotional regulation challenges manifest as an amplification of distress, driven by an intense need for reassurance and closeness.

- Heightened Emotional Expression:

- Intense, Prolonged Tantrums: These aren’t just typical toddler outbursts; they can be unusually long, loud, and difficult to de-escalate, as the child fears their distress won’t be noticed or met.

- Clinginess and Separation Anxiety: Even minor separations can trigger extreme emotional responses, as they constantly seek proximity to confirm the caregiver’s availability.

- Difficulty Self-Soothing: Without a consistent internal model of comfort, they struggle to calm themselves down and rely heavily on others to manage their emotional states.

- “Testing” Behaviors: They might escalate their emotional displays to “test” whether their caregiver will truly stay and respond.

**Avoidant Attachment: Suppression and Emotional Distance**

Conversely, children who develop an avoidant attachment learn early on that expressing their needs or distress often leads to rejection, dismissal, or discomfort from their caregivers. To protect themselves, they learn to suppress their emotions entirely.

- Apparent Emotional Flatness:

- Stoicism: They may appear unusually independent and unfazed by situations that would typically upset other children (e.g., minor injuries, separation from a parent).

- Difficulty Expressing Needs: They rarely ask for help or comfort, even when clearly distressed, having learned that their emotional bids will likely be ignored or rebuffed.

- Internalized Distress: While they may appear calm on the outside, their internal physiological stress markers can be high. They’ve learned to manage their emotions by shutting them down, rather than processing them.

- Early Independence (Self-Reliance): They might demonstrate an advanced, almost performative, level of self-reliance, avoiding intimacy or emotional closeness.

The Broader Impact: A Cascade of Challenges

This inability to effectively manage feelings, whether through amplification or suppression, is profoundly distressing for the child. It can lead to:

- Internal Turmoil: Chronic stress, anxiety, and even physical symptoms like stomachaches or headaches.

- Social Difficulties: Struggles in forming healthy friendships, understanding social cues, and resolving conflicts.

- Academic Challenges: Difficulty concentrating, behavioral issues in the classroom, and reduced capacity for learning when emotionally overwhelmed.

- Long-Term Mental Health Risks: An increased vulnerability to anxiety disorders, depression, and other mental health concerns later in life if these patterns remain unaddressed.

Ultimately, the attachment bond shapes not just how children feel their emotions, but how they learn to live with them, influencing their entire developmental trajectory.

Difficulties in Social Skills and Peer Relationships

Early attachment patterns shape a child’s internal working model of relationships. This model dictates their expectations for how others will treat them. Children with insecure attachments often struggle to form healthy peer relationships. For instance, they may be overly dependent on friends, have trouble trusting others, or misinterpret social cues. An avoidant child might push friends away to maintain emotional distance. Meanwhile, a child with a disorganized attachment may have chaotic and unpredictable social interactions, making it hard to build stable friendships.

Hindered Academic and Cognitive Function

Feeling safe is a prerequisite for learning. Source The chronic stress associated with insecure attachment can interfere with a child’s cognitive development. When a child’s brain is focused on seeking security or managing emotional distress, fewer resources are available for exploration, curiosity, and learning. Consequently, some studies show a link between insecure attachment and difficulties with attention, problem-solving, and overall academic performance . They may find it harder to concentrate in a classroom setting or may be too preoccupied with relationship anxieties to engage with school material.

Long-Term Effects and Seeking Help

The patterns established in early childhood often continue into adolescence and adulthood if left unaddressed. An insecure attachment can increase a child’s vulnerability to mental health challenges later in life, including anxiety, depression, and personality disorders. It can also make it difficult to form and maintain stable, healthy romantic relationships in adulthood.

**Key Warning Signs to Watch For**

Understanding attachment difficulties requires careful observation of your child’s behavior across different situations and relationships. These signs often manifest in subtle ways that can be easily overlooked or misinterpreted as typical childhood phases.

**Emotional and Behavioral Red Flags**

- Extreme reactions to separation – Your child may become inconsolable when you leave for work, school drop-offs become daily battles, or they panic when you’re out of sight even briefly

- Difficulty forming connections – They struggle to bond with caregivers, teachers, or peers, often appearing distant or indifferent in relationships

- Aggressive or withdrawn responses – Lashing out physically or emotionally when feeling vulnerable, or completely shutting down during stressful moments

- Sleep and eating disruptions – Persistent nightmares, refusal to sleep alone, extreme pickiness with food, or using eating as a control mechanism

**Social Interaction Patterns**

Peer relationships often reveal significant attachment challenges:

- Avoidance of close friendships – Your child may prefer playing alone or struggle to maintain lasting connections with classmates

- Inappropriate boundaries – Either becoming overly clingy with strangers or maintaining rigid distance from everyone

- Difficulty reading social cues – Missing important nonverbal communication, leading to frequent misunderstandings or conflicts

**Academic and Developmental Indicators**

School performance can serve as a crucial window into attachment security:

- Concentration problems – Unable to focus when feeling emotionally unsafe or uncertain about relationships

- Regression in milestones – Previously mastered skills like potty training or language development may temporarily disappear during stress

- Perfectionism or complete disengagement – Either becoming obsessively focused on achievement to gain approval or giving up entirely to avoid potential rejection

**Physical Manifestations**

Somatic symptoms frequently accompany attachment difficulties:

- Frequent headaches or stomachaches without medical cause

- Hypervigilance – constantly scanning the environment for threats or signs of abandonment

- Self-soothing behaviors like thumb-sucking, hair-pulling, or repetitive movements that persist beyond typical developmental stages

**Timeline and Consistency Matters**

The duration and frequency of these behaviors distinguish temporary adjustment issues from deeper attachment concerns. Look for patterns that persist for several weeks or months across multiple environments – home, school, and social settings. Single incidents or brief phases during major life changes are typically normal responses to stress.

- Extreme clinginess or a refusal to be separated from a caregiver.

- An apparent lack of preference for a caregiver over a stranger.

- Difficulty being soothed when distressed.

- Contradictory behaviors (e.g., seeking comfort and then pushing it away).

- Avoidance of physical affection or emotional closeness.

If you notice these signs, seeking professional support is a positive and proactive step. A therapist specializing in child development or attachment can provide guidance and interventions. Therapies like Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) or attachment-focused family therapy can help repair and strengthen the caregiver-child bond.

In conclusion, the impact of insecure attachment on a child’s development is significant, affecting everything from emotional control to social skills. Understanding the different attachment styles—anxious, avoidant, and disorganized—provides insight into a child’s behavior. It is important to remember that these patterns are not a life sentence. With awareness, compassion, and professional support, caregivers can build more secure connections with their children. This effort fosters resilience and lays the foundation for a healthier, happier future.