The bond you share with your child is one of life’s most profound connections. From the very first moments, this relationship begins to form a foundation for their future. This foundation is what psychologists call attachment. Understanding attachment can transform your parenting. It helps you see how your everyday interactions shape your child’s emotional world. Consequently, you can build a relationship that helps them feel safe, understood, and confident.

Gryphon Tower Super-Fast Mesh WiFi Router â Advanced Firewall Security, Parental Controls, and Content Filters â Tri-Band 3 Gbps, 3000 sq. ft. Full Home Coverage per Mesh Router offers advanced controls for managing circle home, giving you comprehensive tools to monitor and limit device usage. Gryphon Tower Super-Fast Mesh WiFi Router â Advanced Fire…. Where learning meets fun provides valuable support and resources for amazon fire, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Where learning meets fun. Don’t Miss a Beat with Stylish & Functional Timers helps you manage and monitor visual timer, providing practical tools to establish healthy boundaries and routines. Don’t Miss a Beat with Stylish & Functional Timers. TickTalk5 Smart Watch for Kids with GPS Tracker, Video Calling, Texting, and Parental App, 4G Smartwatch with Free Music, Phone Calls, and Reminders for Kids Ages 3-12 provides a physical solution for managing kids smartwatch, helping you create intentional boundaries and reduce distractions. TickTalk5 Smart Watch for Kids with GPS Tracker, Video Ca…. JoyCat Kids Learning Tablet: 156 Pages Tap-to-Read Flash Cards with 20 Listen & Find Games, Montessori Toy for Alphabet, Phonics, Words, Simple Math, Colors, Shapes & Songs – Autism Gifts (Ages 2-6) provides valuable support and resources for carrots cake, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. JoyCat Kids Learning Tablet: 156 Pages Tap-to-Read Flash …. Small Weekly Calendar Dry Erase Whiteboard for Wall, 16″ x 12″ Magnetic Dry Erase Board, Hanging Double-Sided White Board, Portable Board for List, Kitchen, Planning, Memo, Home, Office provides valuable support and resources for family schedule, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Small Weekly Calendar Dry Erase Whiteboard for Wall, 16″ …. 3 Pack Kid Blue Light Glasses For Kids Girls Boys Computer Blue Light Kids Glasses Clear Glasses Age 3-9 (Black + Dark blue + Light blue) protects your eyes from harmful blue light exposure, reducing eye strain and supporting better sleep quality during screen time. 3 Pack Kid Blue Light Glasses For Kids Girls Boys Compute…. Timed Lock Box-Boost Your Mental Wellness provides valuable support and resources for phone lockbox, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Timed Lock Box-Boost Your Mental Wellness. Protect Your Network with Cutting-Edge Firewalls provides valuable support and resources for router parental, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Protect Your Network with Cutting-Edge Firewalls. Screen Time Tokens – Clip To Rewards – Behavior Management Tool – Positive Reinforcement helps you manage and monitor screen time, providing practical tools to establish healthy boundaries and routines. Screen Time Tokens – Clip To Rewards – Behavior Managemen…. MSTJRY Charging Station for Multiple Devices : 6 Port USB Charger Stations – Family Multi-Device Organizer Charging Dock – Designed for iPhone iPad Android Cell Phone Tablet and Electronic, Black provides a physical solution for managing phone charging, helping you create intentional boundaries and reduce distractions. MSTJRY Charging Station for Multiple Devices : 6 Port USB…. Hands-On Learning, Without the Screen provides valuable support and resources for educational apps, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Hands-On Learning, Without the Screen. The Attachment Theory Workbook: Powerful Tools to Promote Understanding, Increase Stability, and Build Lasting Relationships (Attachment Theory in Practice) provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through attachment theory challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. The Attachment Theory Workbook: Powerful Tools to Promote…. How To Heal An Anxious Attachment Style: A Self Therapy Journal to Conquer Anxiety & Become Secure in Relationships provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through healing anxious challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. How To Heal An Anxious Attachment Style: A Self Therapy J…. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized Attachment Recovery Workbook: Apply Attachment Theory to Understand Your Behavior Patterns, Improve Emotional Regulation, and Build Secure & Healthy Relationships provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through avoidant disorganized challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. Anxious, Avoidant, and Disorganized Attachment Recovery W…. Overcoming Insecure Attachment: 8 Proven Steps to Recognizing Anxious and Avoidant Attachment Styles and Building Healthier, Happier Relationships provides valuable support and resources for insecure to, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Overcoming Insecure Attachment: 8 Proven Steps to Recogni…. Disorganized Attachment: Move Beyond Your Fear of Abandonment, Intimacy, and Build a Secure Love Connection provides valuable support and resources for disorganized attachment, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Disorganized Attachment: Move Beyond Your Fear of Abandon…. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It …. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment styles, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It …. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. When Emotions Are Intense, You Need The Right Tool. The Attachment Theory Journal: Prompts and Exercises to Promote Understanding, Increase Stability, and Build Relationships That Last (Attachment Theory in Practice) provides practical exercises and insights to help you understand and work through attachment theory challenges, offering structured guidance for personal growth and healing. The Attachment Theory Journal: Prompts and Exercises to P…. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications offers comprehensive information and strategies for navigating attachment theory, providing valuable insights and practical advice for your journey. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Ap…. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love provides valuable support and resources for attachment theory, offering practical tools and insights to help you on your journey. Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It ….

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Understanding how children form connections is fundamental to their healthy development. This exploration will delve into the profound impact of early relationships, highlighting how they shape a child’s sense of self and their ability to relate to others throughout life.

The Foundation: What is Attachment Theory?

At its heart, attachment theory posits that humans have an innate, biological need to form close emotional bonds with primary caregivers. Developed by psychologist John Bowlby and further expanded by Mary Ainsworth, this theory isn’t just about love; it’s about survival.

- Seeking Proximity: From birth, infants are wired to seek proximity to a trusted adult, especially when they feel threatened, scared, or in need of comfort. This “attachment system” ensures their safety and well-being.

- The Caregiver’s Role: The parent or primary caregiver acts as a “secure base” from which the child can explore the world and a “safe haven” to return to for comfort and reassurance.

- Internal Working Models: Through repeated interactions, children develop “internal working models” – unconscious blueprints or expectations about how relationships work, how worthy they are of love, and how responsive others will be to their needs. These models profoundly influence future relationships.

Exploring the Spectrum: Early Childhood Attachment Styles

The quality of a child’s early interactions with their primary caregiver shapes their unique attachment style. These styles are patterns of relating that emerge in infancy and early childhood, influencing how children perceive themselves, others, and the world.

Here are the main attachment styles observed in young children:

- Secure Attachment:

- Characteristics: Children with secure attachment feel confident exploring their environment, knowing their caregiver is a reliable source of comfort. They may be upset when the caregiver leaves but are easily soothed upon their return, seeking contact and quickly resuming play. They trust their caregiver to meet their needs.

- How it Forms: This style develops when caregivers are consistently responsive, sensitive, and available to their child’s emotional and physical needs. They provide comfort, support, and reassurance.

- Insecure-Avoidant Attachment:

- Characteristics: These children may appear overly independent. They often show little distress when the caregiver leaves and actively avoid or ignore them upon their return. They may seem unfazed, even when experiencing internal stress, and tend to suppress their emotions.

- How it Forms: This can arise when caregivers are consistently unavailable, unresponsive, or dismissive of the child’s needs, especially emotional ones. The child learns that expressing needs doesn’t lead to comfort, so they minimize emotional displays.

- Insecure-Ambivalent (or Anxious-Preoccupied) Attachment:

- Characteristics: Children with this style are often highly distressed when the caregiver leaves and may be difficult to soothe upon their return. They might seek comfort but then resist it, appearing angry or passive. They often seem anxious and clingy, struggling to explore independently.

- How it Forms: This style often results from inconsistent caregiving – sometimes responsive, sometimes intrusive, sometimes unavailable. The child learns that their needs might be met, but it’s unpredictable, leading to heightened anxiety and an exaggerated attempt to gain attention.

- Disorganized Attachment:

- Characteristics: This is the most complex style, characterized by a lack of a clear, coherent strategy for coping with stress. Children may exhibit contradictory behaviors, such as approaching the caregiver while simultaneously looking away, freezing, or showing fear. Their behavior seems confused and disoriented.

- How it Forms: Often linked to frightening or inconsistent caregiver behavior, such as abuse, neglect, or unresolved trauma in the caregiver that leads to unpredictable responses. The caregiver is simultaneously a source of comfort and fear, creating an unsolvable dilemma for the child.

Building Bonds: Practical Ways to Nurture a Secure Attachment

The good news is that attachment is not set in stone, and even if early experiences weren’t ideal, parents can still work towards fostering a more secure bond. Here are actionable strategies to nurture a strong, secure connection with your child:

- 1. Be Present and Attentive:

- Tune In: Actively observe your child’s cues – their facial expressions, body language, sounds, and words. What are they trying to communicate?

- Put Down Distractions: Make eye contact, get down to their level, and engage fully during playtime, feeding, and comforting moments. Your undivided attention sends a powerful message of worthiness.

- 2. Respond Consistently and Sensitively:

- Meet Needs Promptly: Especially for infants, responding quickly to cries for hunger, discomfort, or fear builds trust. You can’t “spoil” a baby by meeting their needs.

- Validate Emotions: When your child is upset, acknowledge their feelings rather than dismissing them. “I see you’re really sad that the toy broke,” or “It’s frustrating when things don’t go your way.” This teaches them that their emotions are valid and you are there to help them navigate them.

- 3. Provide a Predictable and Safe Environment:

- Establish Routines: Predictable daily routines (bedtime, mealtime, play) create a sense of safety and control for children. They know what to expect.

- Be Reliable: Follow through on promises. If you say you’ll be back, be back. This builds trust and reinforces your reliability as a secure base.

- 4. Offer Comfort and Co-Regulation:

- Be a Safe Haven: When your child is distressed, offer physical comfort (hugs, cuddles), gentle words, and a calm presence. Help them regulate their big emotions by staying calm yourself.

- Engage in Play: Play is a child’s language. Join them in imaginative play, follow their lead, and share moments of joy and laughter. This strengthens your bond and creates positive shared experiences.

- 5. Encourage Exploration and Independence:

- Be a Secure Base for Exploration: Allow your child to explore their environment, try new things, and make age-appropriate choices. Let them know you’re there if they need help or reassurance.

- Celebrate Small Victories: Acknowledge their efforts and successes, fostering their self-esteem and confidence in their ability to navigate the world.

- 6. Reflect on Your Own Attachment History (if applicable):

- Understanding your own early experiences can provide insight into your parenting style and help you consciously choose to respond differently if needed. Seeking support from a therapist or parenting coach can be incredibly beneficial.

By consistently offering warmth, responsiveness, and a secure presence, parents can lay the groundwork for a child’s lifelong emotional well-being, fostering resilience, empathy, and the capacity for healthy relationships.

What Is Attachment Theory?

Attachment theory provides a framework for understanding the deep emotional bond between a child and their primary caregiver. Psychologist John Bowlby first developed this theory in the mid-20th century. He proposed that infants have an innate need to seek proximity to a caregiver for safety and comfort, especially when they feel distressed or threatened. This is a fundamental survival instinct.

The Blueprint for a Lifetime of Connections

Think of a child’s first attachment relationship as an emotional blueprint that gets etched into their developing brain. This blueprint becomes the template they unconsciously use to navigate every relationship that follows – from playground friendships to boardroom collaborations, from teenage crushes to marriage partnerships.

The Internal Compass: How Early Bonds Shape Expectations

Children are remarkably perceptive observers, constantly gathering data about how relationships work. Through thousands of daily interactions with their primary caregivers, they develop what psychologists call an “internal working model” – essentially a relationship roadmap that guides their future social navigation.

This internal compass helps children answer fundamental questions about human connection:

- “When I’m upset, will someone comfort me?”

- “If I make a mistake, will I still be accepted?”

- “Can I trust others to be there when I need them?”

- “Do I deserve kindness and patience?”

Real-World Examples of Attachment Blueprints in Action

The Securely Attached Child:

A toddler who consistently receives responsive care learns that relationships are safe harbors. As a teenager, they’re more likely to:

- Communicate openly with friends during conflicts

- Seek help from teachers when struggling academically

- Form healthy romantic relationships built on mutual respect

The Anxiously Attached Child:

A child whose caregiver is inconsistently available may develop a hypervigilant approach to relationships. Years later, they might:

- Constantly seek reassurance from partners

- Interpret neutral facial expressions as signs of rejection

- Struggle with boundaries in friendships

The Ripple Effect Across Decades

The influence of early attachment extends far beyond childhood, creating generational patterns that can persist for decades:

- Friendship Formation

- Securely attached children typically attract and maintain healthier peer relationships

- They demonstrate better conflict resolution skills and emotional regulation

- Academic and Professional Success

- Strong early attachments correlate with better stress management

- These children often show greater resilience when facing challenges

- Future Parenting Styles

- Adults tend to parent the way they were parented, unless they consciously work to break negative cycles

- Secure attachment often breeds secure attachment in the next generation

The Neurological Foundation

During these crucial early years, a child’s brain is developing at an extraordinary pace, forming over one million neural connections per second. The quality of attachment relationships literally shapes brain architecture, influencing:

- Stress response systems that determine how they handle pressure throughout life

- Emotional regulation circuits that affect their ability to manage feelings

- Social cognition networks that help them read and respond to others

This neuroplasticity makes the early years both incredibly vulnerable and remarkably powerful – small, consistent actions by caregivers can have profound, lasting impacts on a child’s entire life trajectory.

The Critical Period for Attachment

While attachment is a lifelong process, the first two years of a child’s life are particularly crucial. During this time, a child’s brain is developing at a rapid pace. Their experiences with caregivers directly wire their neural pathways for social and emotional functioning. A consistent, responsive caregiver helps the child’s nervous system learn to regulate stress. This creates a secure base from which the child can confidently explore the world. Conversely, inconsistent or neglectful care can make it harder for a child to manage their emotions and trust others.

The Four Primary Attachment Styles

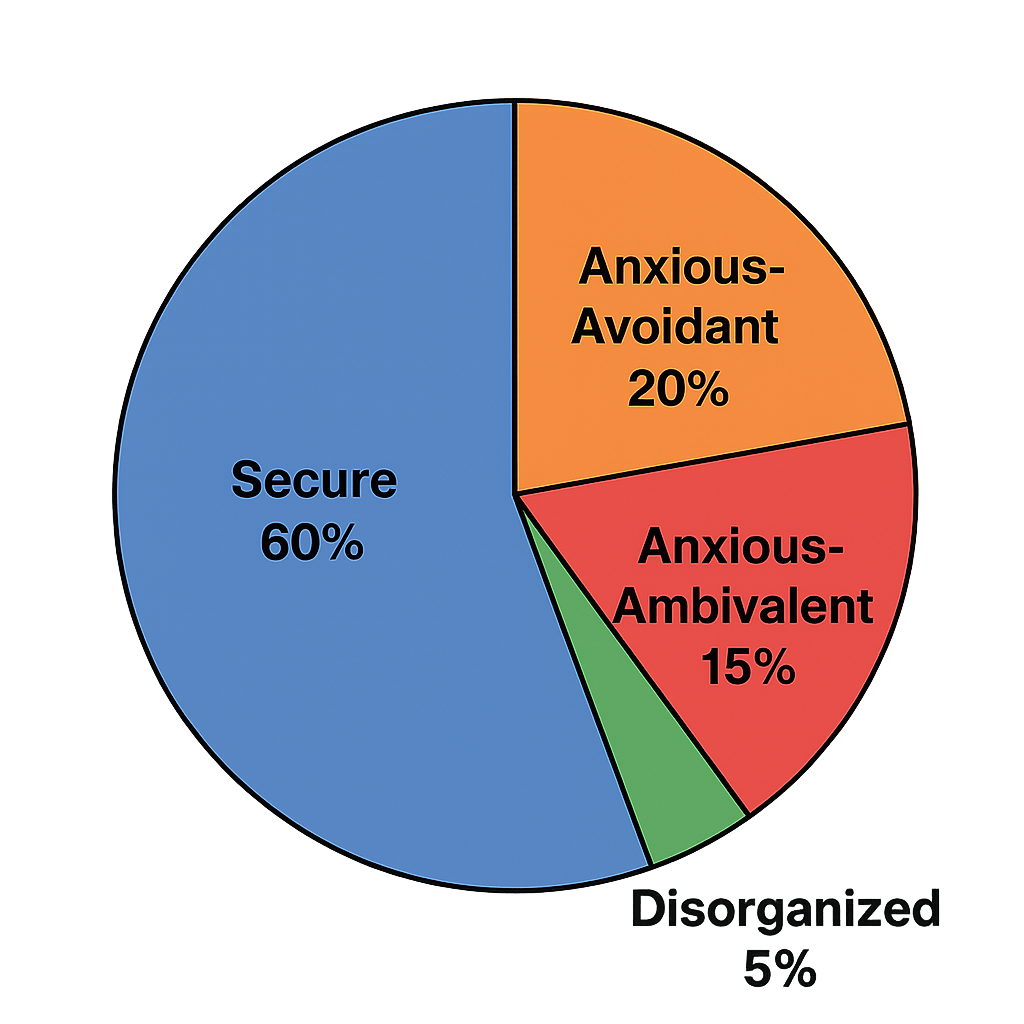

Researchers, most notably Mary Ainsworth, identified four distinct patterns of attachment. Source They observed how young children behaved in a laboratory setting called the “Strange Situation,” which involved brief separations from and reunions with their caregiver. These observations revealed clear differences in how children managed stress and used their caregiver for comfort. Research suggests that about 55-65% of children develop a secure attachment style. The remaining children form one of three insecure styles.

Secure Attachment

A securely attached child feels confident that their caregiver is available and responsive. This security develops when a parent consistently and sensitively meets the child’s physical and emotional needs. For example, they comfort the child when they cry, feed them when they are hungry, and engage in warm, positive interactions.

In the Strange Situation, these children explore the room freely when their caregiver is present. They often become visibly upset when the caregiver leaves. However, upon the caregiver’s return, they actively seek comfort and are quickly soothed. This pattern shows a healthy balance between exploration and seeking connection. These children learn that they can rely on others for help, which builds a foundation of trust and self-worth.

Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment

This style often develops when a caregiver’s responses are inconsistent. Sometimes the parent is attentive and loving, but at other times they are intrusive or ignore the child’s needs. The child learns that they must work hard to get their caregiver’s attention. As a result, they become uncertain if their needs will be met.

Children with an anxious-ambivalent style are often clingy and hesitant to explore. They become extremely distressed when their caregiver leaves the room. When the caregiver returns, the child is not easily comforted. They may simultaneously seek comfort while also resisting it, perhaps by arching their back or pushing the parent away. This reflects their confusion and frustration about the caregiver’s reliability.

Anxious-Avoidant Attachment

The Development of Anxious-Avoidant Patterns

Children with anxious-avoidant attachment styles often grow up in environments where emotional distance becomes the norm. These caregivers may exhibit several characteristic behaviors that inadvertently push their children toward self-reliance:

Common Caregiver Behaviors That Foster Avoidance

- Dismissing emotional expressions: Responding to tears with phrases like “stop crying” or “you’re being too sensitive”

- Prioritizing achievement over connection: Focusing primarily on academic or behavioral performance while overlooking emotional needs

- Modeling emotional suppression: Rarely showing their own vulnerability or discussing feelings openly

- Rushing developmental milestones: Expecting children to self-soothe, sleep alone, or handle challenges before they’re developmentally ready

The Child’s Adaptive Response

When faced with repeated emotional unavailability, children develop sophisticated coping mechanisms:

- Internal shutdown protocols: They learn to recognize early warning signs that their caregiver might become uncomfortable with emotional displays

- Hyper-independence development: These children often become remarkably self-sufficient, sometimes appearing more mature than their peers

- Emotional camouflaging: They master the art of appearing “fine” even when struggling internally

Real-World Manifestations

This attachment style often reveals itself through specific behaviors:

- The “easy” child syndrome: Teachers and other adults frequently praise these children for being low-maintenance

- Difficulty seeking help: Even when struggling academically or socially, they rarely reach out for support

- Emotional flatness: Their emotional range may appear limited, with subdued reactions to both positive and negative events

- Premature caretaking: They might take on responsibilities for younger siblings or even their own parents’ emotional needs

The Internal Experience

Beneath the surface of apparent independence, these children often experience:

- Chronic loneliness: Despite appearing self-sufficient, they may feel profoundly isolated

- Hypervigilance: Constantly scanning their environment for signs of rejection or disapproval

- Internal conflict: Simultaneously craving connection while fearing the vulnerability it requires

This pattern creates a self-perpetuating cycle where the child’s withdrawal confirms the caregiver’s belief that independence is preferable, further reinforcing the emotional distance between them.

In unfamiliar settings, children exhibiting this particular attachment pattern often present a striking picture of self-sufficiency. They are the ones who might immediately plunge into exploration, seemingly unfazed by new faces or surroundings. Instead of periodically checking back with their caregiver for reassurance, they tend to operate as if the adult is merely a background fixture.

The Appearance of Detachment

When their primary caregiver departs, perhaps for a brief period in a “Strange Situation” experiment or simply leaving them at daycare, these children typically display minimal to no overt signs of distress. You won’t see tears, hear cries, or observe them calling out. They may continue playing with toys or interacting with their environment as if the separation hasn’t registered, maintaining a calm, almost indifferent demeanor. This lack of visible reaction can be perplexing to observers, as it deviates significantly from the expected separation anxiety common in securely attached children.

The Active Avoidance of Reconnection

Upon the caregiver’s return, their behavior becomes even more telling. Rather than rushing for a hug or expressing relief, these children often engage in active avoidance. This can manifest in several ways:

- Turning Away: They might physically turn their back to the caregiver.

- Lack of Eye Contact: Deliberately avoiding gaze.

- Intense Focus on Objects: They may suddenly become engrossed in a toy or an activity, using it as a shield to prevent interaction.

- Ignoring Bids for Connection: If the caregiver attempts to initiate contact, the child might continue to act as if they haven’t noticed them, or even walk away.

This isn’t just passive disinterest; it’s a deliberate, albeit subconscious, strategy to minimize interaction and emotional engagement with the returning adult.

The Hidden Internal Turmoil

What’s crucial to understand is that this outward composure is often a facade. While they appear unfazed and emotionally detached, scientific studies employing physiological measures reveal a different internal reality. These children often experience significant internal physiological distress. Research using indicators like:

- Heart Rate Monitoring: Showing elevated heart rates.

- Cortisol Levels: Detecting increased stress hormones.

- Galvanic Skin Response: Indicating heightened arousal.

…demonstrates that their bodies are, in fact, reacting to stress, even if their faces and behaviors suggest otherwise. There’s a profound disconnect between their external presentation and their internal state of arousal.

A Learned Survival Strategy

This seemingly independent and avoidant behavior is not a sign of true resilience or indifference; rather, it’s a deeply ingrained survival strategy. These children have learned from early experiences that expressing their needs, vulnerability, or distress to their caregiver often leads to:

- Rejection or Dismissal: Their bids for comfort might have been consistently ignored or met with irritation.

- Punishment: They may have been subtly or overtly punished for showing emotion or needing closeness.

- Unavailability: The caregiver might have been consistently emotionally or physically distant.

To protect themselves from the pain of rejection and to maintain a sense of predictability in their interactions, they have adapted by suppressing their attachment needs and emotional displays. They learned that it is “safer” to appear self-sufficient and emotionally detached than to risk vulnerability and face potential disappointment or discomfort. This pattern is characteristic of what is known as avoidant attachment – a complex adaptation to an environment where consistent, sensitive responsiveness from the caregiver was often absent.

Disorganized Attachment

Disorganized attachment is the most insecure style. It often arises from caregiving environments that are frightening or chaotic. The caregiver may be a source of both comfort and fear, which is deeply confusing for a child. This can happen in situations involving abuse, neglect, or a caregiver with unresolved trauma.

The child’s behavior reflects this confusion. They lack a coherent strategy for getting their needs met. For instance, they might approach their caregiver but then suddenly freeze, run away, or show other contradictory behaviors. They may seem dazed or disoriented. These children are in an impossible situation: their innate drive to seek comfort from a caregiver conflicts with their instinct to protect themselves from a source of fear.

How to Nurture a Secure Attachment

Building a secure attachment does not require perfect parenting. Instead, it requires being a “good enough” parent who is consistent and sensitive most of the time. The goal is connection, not perfection. Here are some practical ways to foster a secure bond with your child.

Prioritize Responsiveness

Tune in to your child’s cues. Source When they cry, try to understand what they need. Is it hunger, discomfort, or a need for closeness? Responding promptly and warmly teaches your child that they are important and that you are a reliable source of help. This does not mean you will spoil them; it means you are building their trust in the world.

Create Consistent Routines

The Power of Predictable Patterns in Child Development

Routine-based security forms the foundation of healthy emotional development. When children can anticipate what comes next in their day, their nervous systems remain calm and regulated. This predictability manifests in several key areas:

Daily Structure That Builds Trust

Morning rituals create a launching pad for the day:

- Consistent wake-up times followed by the same sequence of activities

- Predictable breakfast routines where children know their preferred foods will be available

- Regular morning conversations or songs that signal the start of a new day

Meal patterns that extend beyond just timing:

- Familiar plates, cups, and utensils that feel comforting

- Consistent seating arrangements that create a sense of belonging

- Predictable food introduction methods that reduce anxiety around new experiences

Bedtime sequences that signal safety and closure:

- The same order of activities: bath, story, songs, or quiet conversation

- Consistent lighting patterns that help regulate circadian rhythms

- Reliable comfort objects and sleeping environments

Emotional Consistency: Your Internal Weather System

Your emotional availability serves as your child’s internal compass. Children are remarkably attuned to the emotional climate you create, and they use this information to gauge their own safety levels.

Regulated responses during challenging moments:

- Maintaining calm energy even when addressing difficult behaviors

- Using consistent language patterns for comfort and correction

- Offering predictable physical comfort through hugs, gentle touches, or simply being present

Emotional transparency that builds security:

- Acknowledging your own feelings in age-appropriate ways

- Demonstrating healthy emotional regulation through your actions

- Showing consistent care even during your own difficult moments

The Neurological Impact of Stability

When children experience consistent environmental cues, their developing brains can allocate energy toward growth rather than survival. This biological shift enables:

Enhanced learning capacity through:

- Improved attention spans when anxiety levels remain low

- Better memory formation in secure environments

- Increased curiosity and exploration when safety is guaranteed

Stronger social-emotional skills including:

- Greater empathy development when their own needs are predictably met

- Improved self-regulation abilities modeled through your consistency

- Enhanced communication skills when they trust their expressions will be received warmly

Physical development benefits such as:

- Better sleep quality leading to optimal growth hormone production

- Improved digestive health when meal stress is minimized

- Enhanced immune system function in low-stress environments

Creating Flexibility Within Structure

Adaptive consistency means maintaining core predictable elements while allowing for natural variations. This might include:

- Keeping bedtime routines intact even when traveling or during special occasions

- Maintaining your warm, responsive communication style across different settings

- Preserving key comfort rituals while gradually introducing new experiences

This approach teaches children that while life includes changes and surprises, the fundamental safety of their relationship with you remains constant.

Focus on Quality Connection

Creating Meaningful Connection Through Intentional Presence

Digital boundaries become essential when building secure attachment with your child. Consider implementing specific phone-free zones and times:

- Morning connection ritual: Start each day with 15 minutes of undivided attention before checking devices

- Meal times: Keep phones in another room to focus entirely on conversation and shared experiences

- Bedtime routine: Create a sacred wind-down period free from digital distractions

- Car rides: Use travel time for singing, storytelling, or simply talking about the day

The Science Behind Eye Contact and Facial Expression

When you make direct eye contact with your child, you’re activating their mirror neuron system, which helps them:

- Learn emotional regulation by observing your calm, loving expression

- Develop empathy through facial mimicry and emotional attunement

- Build trust as they see themselves reflected positively in your eyes

- Strengthen neural pathways associated with social connection and security

Your genuine smile triggers an immediate response in your child’s brain, releasing dopamine and creating positive associations with your presence. This neurological dance happens within milliseconds but creates lasting imprints on their developing attachment system.

The Power of Musical Connection

Singing together creates unique bonding opportunities that go beyond simple conversation:

- Lullabies and gentle songs regulate your child’s nervous system through rhythm and melody

- Action songs like “Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes” combine physical touch with vocal connection

- Made-up silly songs about daily activities (getting dressed, brushing teeth) turn routine moments into joyful exchanges

- Cultural or family songs pass down heritage while creating shared identity

The synchronized breathing that occurs during singing naturally calms both parent and child, creating an optimal state for bonding.

Everyday Conversations That Build Security

Narrating your child’s world helps them feel seen and understood:

- Describe what they’re experiencing: “I see you’re really concentrating on stacking those blocks”

- Acknowledge their emotions: “You seem frustrated that the puzzle piece won’t fit. That’s hard!”

- Share your own appropriate feelings: “I feel so happy when we read stories together”

- Ask open-ended questions: “What do you think will happen next in our story?”

These verbal acknowledgments help children develop emotional vocabulary and feel validated in their experiences.

The Oxytocin Connection: Your Body’s Bonding Chemistry

Every positive interaction triggers a biochemical cascade that strengthens your relationship:

For your child:

- Oxytocin promotes feelings of safety and trust

- Reduced cortisol levels decrease stress and anxiety

- Enhanced dopamine creates positive associations with your presence

For you as the parent:

- Increased oxytocin enhances your intuitive responses to your child’s needs

- Lowered stress hormones improve your patience and emotional availability

- Strengthened neural pathways make nurturing behaviors more automatic

Transforming Ordinary Moments into Connection Opportunities

Micro-moments throughout the day become building blocks for secure attachment:

- Getting dressed: Make it playful with peek-a-boo games or silly voices

- Diaper changes: Use this time for gentle massage, songs, or animated facial expressions

- Grocery shopping: Point out colors, count items together, or create simple games

- Waiting in line: Practice deep breathing together or play “I Spy”

- Household chores: Turn cleaning into a dance party or sorting game

The Compound Effect of Consistent Connection

These seemingly small interactions create a relationship bank account where:

- Daily deposits of positive attention build emotional reserves

- Consistent responsiveness teaches your child they can count on you

- Accumulated trust helps your child navigate challenges with confidence

- Secure base behavior develops as your child learns you’re a reliable source of comfort and support

Remember: Quality trumps quantity. Five minutes of fully present, engaged interaction carries more weight than an hour of distracted, half-hearted attention.

Final Thoughts: The Power of Your Presence

Understanding attachment styles is not about labeling your child or judging your parenting. Rather, it is a tool that illuminates the profound importance of your role as a caregiver. The bond you build in these early years provides your child with a blueprint for emotional health that can last a lifetime. Remember that attachment is a dynamic process, and relationships can heal and grow over time.

Ultimately, fostering a secure attachment comes down to being present, sensitive, and loving. Your consistent care communicates a powerful message to your child: you are safe, you are loved, and you can count on me. This message is the greatest gift you can give them.